Back in the old days, when people collected their water with pails and tossed waste out the door, life was messy. With the advent of modern plumbing, chores and sanitation became more convenient, and public health improved significantly. Today, OWASA maintains about 350 miles of underground wastewater pipes, connecting to every home, school and business across Carrboro and Chapel Hill.

Running parallel to the drinking-water supply system is a separate wastewater collection system, which transfers used water and domestic sewage to the wastewater treatment plant. The pipes utilize the forces of gravity (with some help from 21 pumping stations) to safely guide our wastewater to the plant, where it’s cleaned and either used as reclaimed water or returned to the water cycle at Morgan Creek, a tributary leading to Jordan Lake.

The wastewater system, while somewhat invisible, has a major presence in the community. If you look down when walking along the street, what do you normally see? Not a wastewater pipe, but probably a manhole. For maintenance or emergency, OWASA can access this critical piping network anywhere in the community through nearly 11,000 manholes.

Want to learn more? Follow the links below to take a deep dive into wastewater treatment.

Wastewater Management

How & Why

Where Does It All Go?

The world does not create new water. All the water on the planet has been recycled for millennia after millennia. So, when we use water, whether for washing dishes or flushing our toilets, where does all that water go?

OWASA ensures its cleanliness and quality, even after it’s been utilized by the community. And that’s where wastewater treatment comes in.

“Our wastewater treatment system is really a resource-recovery system,” says Wil Lawson, Director of Wastewater Management.

miles of wastewater pipes

pumping stations

miles of pressurized pipes

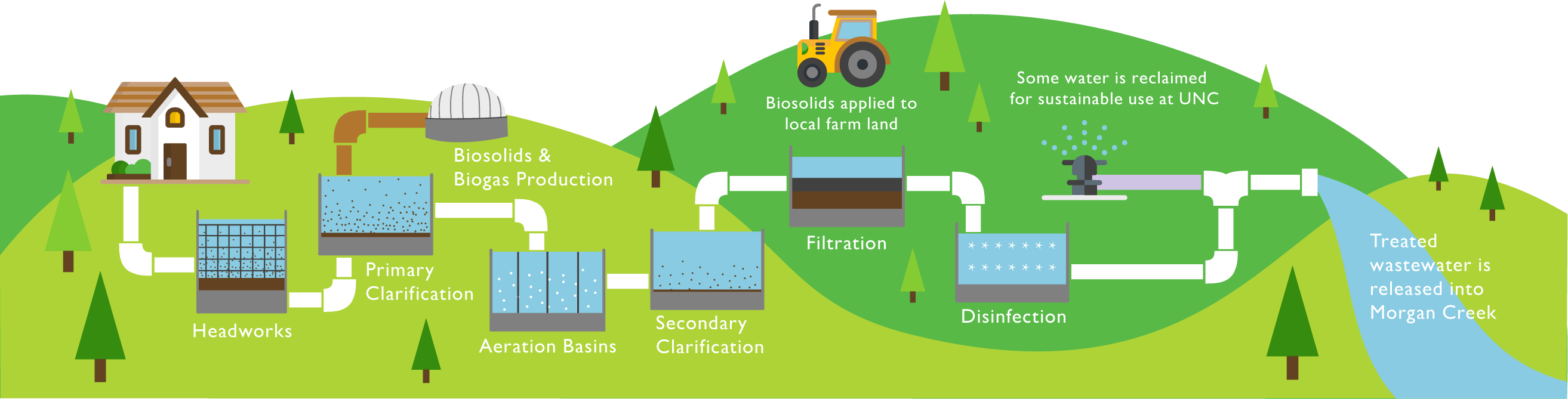

After going down the drain, a system of over 350 miles of wastewater pipe, 21 pumping stations and some 14 miles of pressurized pipes transfer wastewater from our homes and businesses to the Mason Farm Wastewater Treatment Plant near Finley Golf Course in Chapel Hill. The plant can treat up to 14.5 million gallons per day (mgd), but the daily average hovers around 8 mgd.

There, any debris, waste and contaminants the community has contributed to the water supply are removed through a series of physical, chemical, and biological processes before the water is returned to its never-ending cycle.

THE TREATMENT PROCESS

The wastewater treatment can be divided into a few steps:

What Not to Put Down the Drain

Preserving our wastewater system is just as important as protecting our drinking water. Flushing the wrong stuff can harm the wastewater system by causing costly and messy clogs, and even impact water quality in our streams and lakes. Ensuring the high quality of our water supply and preventing wastewater blockages, backups and overflows requires due diligence from all of us.

Our wastewater system and treatment plant are designed to collect and treat water that has been used for toilet flushing, bathing, washing clothes and dishes, food prep, routine cleaning and other normal residential, business and institutional purposes. This is a friendly reminder that the three Ps are the only things that should be flushed down the toilet: Pee, Poo and toilet Paper!

The wastewater system should not be used to dispose of:

- Fat, oil & grease

- Fruit & vegetable matter

- “Flushable” wipes

- Dental floss

- Pet litter

- Condoms, tampons and other personal products

- Fuel or any other petroleum products

- Anything potentially poisonous, explosive or flammable

- Medicines and other pharmaceuticals

The Chapel Hill and Carrboro Police Departments have no-questions-asked “drop box” programs for safe disposal of unused medication.

LEARN MORE

Fat, Oil & Grease

When thinking of the effects of fat, oil and grease in the wastewater system, consider your own body. Just like within our arteries, fat, oil and grease accumulates within pipes, hardening to a plaster-like consistency and causing blockages, backups and overflows. We clean much of our system of 300-plus miles of sewers each year, but it is not possible to remove all fatty accumulations before they can cause overflows.

Try to prevent fat, oil and grease from going down the drain during food preparation and while washing dishes. One easy way to do this is to scrape or wipe fat, oil and grease off pots, pans, plates, bowls or utensils with a paper towel.

If you’re a residential customer, you can put small amounts of fat and solidified grease (one quart or less) in a sealed container for disposal with other household trash. Used cooking oil should be recycled at Orange County’s Household Hazardous Waste program at 1514 Eubanks Rd. in north Chapel Hill. Please call 919-968-2788, send an email to recycling@orangecountync.gov or visit their website for more information.

Businesses must have a grease trap which keeps fat, oil and grease from going into the sewer system and which is regularly cleaned out by a company that recycles fat, oil and grease.

In Case of a Wastewater Overflow

Water seeping out from underneath a manhole signals a wastewater overflow. Overflows are caused by blockages, a huge influx of stormwater, malfunctions at a pumping station or a broken sewer line. Any of these causes is cause enough to contact us at OWASA.

As an overflow is constituted of untreated wastewater, it’s considered a water emergency. If left undiscovered, overflows can return wastewater to the environment or the drinking water supply, causing gastrointestinal illnesses and problems for aquatic life.

To report a wastewater overflow or other emergency, call us at (919) 968-4421. If after normal business hours, follow the directions in our recorded message.

Easements

Some of you may have a 30-foot-wide strip of land behind your property called an easement. But what is an easement?

An easement is an area of clear access to the wastewater system, where we have the right to enter, maintain, repair, inspect, improve, renovate and replace facilities, including pipes and manholes. About half of our sewers are in easements in off-street areas; the other half of our sewers are in public street rights-of-way, which normally include several feet on each side of the street or roadway.

We clear and maintain easements for multiple reasons:

- To prevent tree and shrub roots from entering cracks and joints in sewer mains. When roots grow into a sewer, they grow into a dense mass that will block the flow of wastewater and cause it to overflow from a manhole or possibly inside a residence.

- To help us get to a sewer quickly if there is a wastewater overflow. When overflows occur, we work to stop them quickly to prevent environmental damage.

- To ensure that we will have safe, practical access when other repairs, inspections or improvements are needed.

If there are public wastewater manholes or an OWASA main on or within about 15 feet of your land, it is safe to assume that at least part of an easement is on your land. The presence of an easement does not change the basic ownership of land. However, you will be limited in some ways by the presence of an easement.

For one, we clear about 20 feet of 30-foot-wide easement, so planting is only feasible in the outer five feet on your side of the easement. Secondly, you should only plant trees and groundcover that are shallow-rooted, drought-resistant, native/non-invasive and inexpensive. Here are some perfect examples:

- Bayberry

- Baccharis

- Beauty berry

- Button bush

- Dogwood

- Downy arrowhead

- Redbud

- Red buckeye

- Red cedar

- Silky dogwood

- Smooth sumac

- Sweet shrub

- Toothache tree

- Wild indigo

Finally, we do allow gates to be built on easements, but they must be centered in the easement, easy to open and 12 feet wide. However, we do not allow fences to be built, as they block efforts to access and maintain the easement.

If you are not sure whether there is an OWASA easement on your land, please email us at info@owasa.org, or call us at 919-968-4421 and ask for an engineering technician. We’ll be glad to check our records and let you know what we find. Please note that we may not have records of some easements, especially where sewers are very old, so we also recommend that you check your property acquisition records to see if there are easements on your land. The location of an easement is normally recorded in the County Registry of Deeds with a document called a “plat” showing the boundary of any easement.

Odor Elimination Program

It’s a natural fact: Raw wastewater doesn’t smell nice. But we at OWASA have addressed this problem, and over the past years, we’ve worked hard in trying to eliminate off-site odors from the Mason Farm Wastewater Treatment Plant.

Since 2000, we have invested about $9 million in odor-elimination improvements. The OWASA Board of Directors also adopted in 2004 a resolution reaffirming OWASA’s goal of having no off-site objectionable odors from the plant.

Major completed projects include: four studies to assess and determine the appropriate remedial actions for odor sources; construction of a biofilter to treat exhaust air from the wastewater solids handling facility; covering the solids storage basins and treating the exhaust air through a scrubber; establishing an in-house odor monitoring program (including installation of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) monitors at various locations for automated monitoring and an alarm system for odors related to H2S); covering the headworks (where wastewater enters our plant) and treating headworks exhaust; covering and treating exhaust air with carbon filters at the influent and effluent splitter boxes leading to and from the primary clarifiers, tanks at the intermediate pump station, aeration basin influent channel and all three primary settling tanks; and covering and treating exhaust air from 10 of the plant’s 16 biological treatment tanks.

To report odor from our Mason Farm Wastewater Treatment Plant, please call 919-537-4376 at any time.

Biosolids Recycling Program

As part of our wastewater treatment process, OWASA produces biosolids for land application and agricultural use.

We value the relationship we have with our farmers. Our partnership means that farmers don’t have to resort to using commercial fertilizers, and this beneficial resource is put to good use.

Biosolids are a nutrient-rich byproduct of wastewater treatment. Solids are removed from the wastewater treatment process, which undergo a high-temperature anaerobic digestion process to destroy pathogens and eliminate odors, producing biosolids.

The wastewater treatment plant produces about four dry tons of biosolids each day, which are treated according to Federal and State requirements allowing their beneficial reuse as a fertilizer and soil amendment. Some of this is applied in liquid form to agricultural land, and a portion is “dewatered” to the texture and consistency of moist soil and transported to a private composting facility in Chatham County.

Regulations specify the “agronomic rates” at which biosolids may be land-applied for designated crops; that is, the maximum amount of biosolids that can be applied to a given field is determined by the nitrogen content of the biosolids. We closely monitor the application rates on each individual field and, historically, have applied at rates well below those allowed by regulation.

Based on its high quality and low level of bacteria, OWASA’s biosolids are certified as Class A. Also, Federal and State regulations specify upper concentration limits for selected trace metals in biosolids, such as cadmium, lead, zinc, mercury and more; all OWASA biosolids meet the trace metal requirements necessary to qualify for the Exceptional Quality (EQ) designation of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the NC Division of Water Quality. Our ability to consistently meet these low levels of trace metals reflects the lack of industrial dischargers to our community sewer system.

OWASA staff continues to follow the development of alternate technologies available for the management of biosolids. Our current goal is to continue the work to optimize the land application program while managing limitations with staffing, equipment, weather impacts, land availability and regulations.

For more information, read the EPA’s rules on biosolids.

Substances of Special Interest

OWASA’s extensive wastewater treatment process removes debris, waste and contaminants before returning the effluent – wastewater transformed into treated water – back to local waterways. Yet, there are some human-made substances which remain in wastewater effluent that may of special interest to our customers.

Microbeads

Microbeads are tiny, synthetic plastic particles that were included in toothpaste, soap, cosmetics, exfoliants and other cleansers. Microbeads are sometimes too small to be removed during wastewater treatment, so they can reach streams, creeks and lakes receiving treated wastewater. Unfortunately, these pinhead-sized particles can absorb pollutants, and they are often mistaken as food by fish and other aquatic life.

The federal government introduced the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015 on December 28 of that year. The law bans the manufacture of rinse-off cosmetic products containing plastic microbeads after July 1, 2017, and prohibits the sale of these products after July 1, 2018.

PFAS

PFAS are used in a variety of everyday products to increase resistance to water, grease, or stains such as carpet, clothing, fabric for furniture, paper packaging for food, cookware and other materials. As these materials degrade, they enter household and industrial discharge pathways to wastewater. It is important to OWASA to share information with our community about PFAS throughout our system, from our raw water sources to our wastewater treatment byproducts.

We developed a new web hub to make access to PFAS information easier for our customers: PFAS And Your Water